The US Navy is building a fleet of small unmanned vessels to

act as pickets and outer escorts for carrier and surface groups despite having

no evidence, whatsoever, that the unmanned vessels can effectively carry out

their task. Since the Navy refuses to

conduct any actual experimentation to validate the concept prior to committing

to production, is there any other source of information that might allow us to

assess the concept? Of course there is

and it’s our most reliable source … history!

Specifically, it’s the battle for Okinawa and the role of the Kamikaze

and the US Navy picket ships.

Okinawa was a major battle for both the US and Japan. US losses during the 3 month battle were steep

with 768 aircraft lost in addition to staggering naval losses.(5) From Wikipedia:

At

sea, 368 Allied ships—including 120 amphibious craft—were damaged while another

36—including 15 amphibious ships and 12 destroyers—were sunk during the Okinawa

campaign. The US Navy's dead exceeded its wounded, with 4,907 killed and 4,874

wounded, primarily from kamikaze attacks. (5)

Just as astounding to us, today, was the magnitude of the

forces assembled for the battle. Consider

this partial Allied naval order of battle at Okinawa (1)

US Navy combat ships:

11 fleet

carriers

6 light

carriers

22 escort

carriers

8 fast battleships

10 old battleships

2 large cruisers,

12 heavy

cruisers

13 light

cruisers

4 anti-aircraft light cruisers

132 destroyers

45 destroyer

escorts

Amphibious assault vessels:

84 attack

transports

29 attack cargo

ships

LCIs, LSMs, LSTs,

LSVs, etc.

Auxiliaries:

52 submarine

chasers

23 fast minesweepers

69 minesweepers

11 minelayers

49 oilers

Royal Navy combat ships:

5 fleet carriers

2 battleships

7 light cruisers

14 destroyers

The 265 US combat ships, alone, nearly equals the size of

our entire present day fleet and that was just the force for a single

operation. We’ve truly forgotten the size of the force necessary to wage total

war.

Japan, too, fielded a large force, mainly aerial, along with

the battleship Yamato, a cruiser, and several destroyers. During the course of the battle, Japan

launched 10 large scale kamikaze attacks against the US Navy Fifth Fleet

guarding the Okinawa amphibious invasion fleet.

Each attack consisted of hundreds of aircraft. For example, the first attack consisted of

355 kamikaze aircraft and 344 escort fighters and lasted for five hours. The US Combat Air Patrol (CAP) did an amazing

job but could not stop every attacker.

Twenty-two

kamikazes penetrated the combat air patrol shield on April 6, sinking six ships

and damaging 18 others. Three hundred fifty U.S. crewmen died. (2)

Only 22 attacking aircraft managed to penetrate the aerial

defenses but the damage they did was enormous.

What was the overall result of the kamikaze attacks?

The

Japanese fell short of their goal of “one plane one ship,” but sank 36 American

warships, and damaged 368 other vessels at Okinawa. The Navy’s losses were the

highest of the Pacific war: 4,907 sailors and officers killed, and 4,824

wounded. Japan lost an estimated 1,600 suicide and conventional planes at

Okinawa. (2)

The sheer number of attacking aircraft represented what we

would, today, call a saturation attack intended to overwhelm the defensive

capacity of the US fleet.

The Navy’s answer to the kamikaze saturation attacks was to

establish a ring of radar picket ships around the island and the invasion fleet

extending out as far as 80 miles. The

pickets provided early warning, fighter direction, and direct engagement. Each picket ship was tied to a circular

station of 5000 yds radius.

Wikipedia describes the Okinawa radar picket system.

A

ring of 15 radar picket stations was established around Okinawa to cover all

possible approaches to the island and the attacking fleet. Initially, a typical

picket station had one or two destroyers supported by two landing ships,

usually landing craft

support (large) (LCS(L))

or landing ship

medium (rocket) (LSM(R)),

for additional AA firepower. Eventually, the number of destroyers and supporting

ships were doubled at the most threatened stations, and combat air patrols were provided as well. In early 1945, 26 new construction Gearing-class

destroyers were ordered as

radar pickets without torpedo tubes, to allow for extra radar and AA equipment,

but only some of these were ready in time to serve off Okinawa. Seven destroyer escorts were also completed as radar pickets. The radar picket mission was

vital, but it was also costly to the ships performing it. Out of 101 destroyers

assigned to radar picket stations, 10 were sunk and 32 were damaged by kamikaze

attacks. The 88 LCS(L)s assigned to picket stations had two sunk and 11 damaged

by kamikazes, while the 11 LSM(R)s had three sunk and two damaged. (3)

|

Okinawa Picket Stations

|

Note: Some picket diagrams show a 16th

station located near station 12.

Understanding the basics of the situation at Okinawa, what

can we learn that is applicable to today’s Navy? The foundation of any analysis is the

recognition that the Kamikaze was the functional equivalent of a guided anti-ship

missile. The guidance, obviously, was in

the form of a human pilot and the ‘missile’ was very powerful, rivaling a

modern guided missile in terms of destructive impact. This functional equivalency allows us to

assess the attacks and defense in modern terms.

Further, the dynamic of the Kamikaze and the picket ships gives us

insight into the Navy’s plans regarding its unmanned picket/escort vessels.

As you recall from previous posts, the Navy intends to

procure two types of unmanned vessels.

One will be a small version which is intended to act as a picket for a

larger group by providing surveillance and reconnaissance – much the same as

the picket ships did at Okinawa. The

second will be a somewhat larger vessel which is intended to stay with the main

group and act as a missile barge.

So, what does the Okinawa Kamikaze and picket ship scenario

tell us about the Navy’s plans for its unmanned vessels today? There are several lessons, factors, and

considerations for us.

Lethality – We

need to recognize that today’s anti-ship missile will be every bit as lethal,

if not more so, than the Kamikazes. In

fact, the situation is far worse today due to the complete absence of armor on

modern ships. The Okinawa picket ships

routinely absorbed multiple hits, kept fighting, and often survived. Does anyone seriously believe that a Burke,

FFG(X), or LCS can take multiple hits and not sink? Astonishingly, one of those ships is actually

designed to be abandoned at the first hit!

A missile attack against our ships will be devastating and we need to

factor that into our ship designs and cost and we need to accept that naval

battles will involve a significant degree of attrition. The lethality will absolutely stun us.

Saturation – The Kamikaze

was used as a saturation attack with each of ten major attacks consisting of several

hundred aircraft. This is a lesson we

have completely forgotten. Peer warfare

requires huge numbers of munitions – dwarfing any estimates we may have. This was demonstrated time and again in WWII

and Korea where munition expenditures far exceeded predictions. We’ve become so used to the small Tomahawk

strikes against unresisting targets that we’ve come to believe that peer warfare

will involve the same minimal usage of weapons.

Nothing could be further from the truth.

We’ll see unimaginably massive expenditures of weapons against us and

unbelievable salvos launched against our fleets. We absolutely must come to terms with this

reality because it drives our ship design sensor and weapons density, fire

control capacities, sensor design, armor considerations, etc. Ships with one CIWS will not survive

saturation attacks. We must heavily arm

our ships – far beyond anything imagined by today’s designers.

Defensive Guidance/Sensors

- Defending ships at Okinawa did not possess any weapon guidance comparable to

the Kamikaze pilots and this put them at a huge disadvantage. The defending weapons were optically (and

radar, to a degree) aimed and fuzed to a marginally successful degree. The mismatch in technology between the advanced

[human] guidance of the Kamikazes and the unguided defensive weapons mimics and

demonstrates the consequences of a loss of defensive sensors and fire control

in modern engagements. Given the very limited

number of sensors and fire controls on modern ships, it is all too easy to

imagine a ship being blinded early in an engagement and being unable to

continue fighting even though the weapons, themselves, might still be

available. We desperately need to

increase the number of sensors (redundancy) and types of sensors on our ships. For example, we should have much more

extensive, physically distributed EO/IR sensors tied into the fire control

system as well as a separate, technologically dissimilar type of radar as a

backup to the Aegis arrays. The Aegis

arrays are large, exposed targets and likely to be seriously damaged and

degraded from almost any hit. Consider

the Burke destroyer that was involved in the collision with a commercial ship. One of its radar arrays was, apparently,

rendered completely inoperative and that was from a waterline collision, not a

missile hit. In like fashion, the Port

Royal’s arrays were reportedly rendered inoperative when it gently nosed

aground off Pearl Harbor. That doesn’t

bode well for the combat resilience of the Aegis system. We need sensor redundancy and backups.

Armament – The use

of picket ships mimics the Navy’s desire for advanced screens of unmanned

vessels. The pickets succeeded in their

mission but were devastated – what does that suggest for today’s unmanned

vessel screens? The picket ships were

heavily armed and armored but were still devastated. The Navy, in contrast, envisions the unmanned

escorts being unarmed. They’ll be

quickly eliminated in any combat which will transfer the burden of their

functions back to the manned escorts who won’t be trained or proficient at the

functions and certainly won’t be properly positioned.

Armor – The

Okinawa picket ships were all armored to varying degrees. Again, the Navy envisions completely

unarmored, unmanned vessels as pickets.

Not only will the unmanned vessels be quickly eliminated but the absence

of armor ensures that weapon expenditure by the enemy to do so will be

absolutely minimal. One of the major

benefits of the Okinawa pickets was that they soaked up so many of the

Kamikazes. Imagine if each picket had

instantly sunk from a single hit. The

remaining Kamikazes would have been able to continue on to the amphibious

ships, the true targets of the Kamikazes, instead of being wasted against the

pickets.

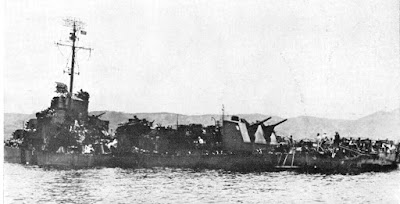

|

| USS Aaron Ward After 6 Kamikaze and 2 Bombs |

Weapon Density –

The number of weapons on the picket ships was incredible and that redundancy

allowed the pickets to keep fighting even after taking multiple hits. The USS Aaron Ward is an outstanding example

of a ship that was able to keep firing despite taking half a dozen or so

Kamikaze strikes and a couple of bomb hits.

Even the ships that would make up today’s core group have very limited

numbers of defensive weapons. While the

VLS numbers are large, and quad packing makes the missile inventory numbers

even larger, we’ve shown that the number of VLS weapons that are actually

usable in an engagement is limited to around four. Beyond that, the number of close in weapons

is nearly non-existent. Burkes have a

single CIWS. Many ships have a single

RAM/SeaRAM. We need to greatly increase

the number of defensive weapons installed on our ships.

Picket Spacing –

One of the aspects that jumps out from looking at the diagrams of the picket

locations is the distances involved. For

those of us who have grown up looking at Navy PR photos of ships sailing side

by side, the idea of spacing is foreign to us.

The Okinawa pickets were located 20-80 miles (mostly 50-80 miles) from

the center of the defended area.

Translating that to modern terms is difficult but one way to sort of get

a handle on it is to compare the Okinawa distancing to the speed of the

incoming attackers. Obviously, the

faster the attacker, the farther out the picket has to be located in order to

provide sufficient warning. At Okinawa,

the pickets were, generally, 50-80 miles from the center point of the defended

area which puts them at distance equivalent to 25% - 40% of the attacking

aircraft’s speed (assuming 200 mph). For

a modern high subsonic (assume 500 mph), anti-ship missile that would,

proportionally, place pickets at 125 miles – 200 miles. That seems unbelievable to us, today, but

facing supersonic or high subsonic missiles, those are the kinds of distances

required to provide sufficient early warning and engagement.

If the Navy intends, as they say, to place unmanned vessels

as escort pickets for the main groups, the pickets will need to be 50-200 miles

out which places them well beyond any AAW support from the core group. As we stated earlier, being unarmed and

unarmored, they’ll die quickly and easily.

I’m pretty sure the Navy hasn’t thought this through.

The Okinawa picket stations were positioned close enough to

allow continuous tracking of attacking aircraft but were too far apart to

provide mutual gun support. Given

today’s longer ranged anti-air missiles, mutual support may be possible but

only if many, many more pickets are used due to the greater required distancing

from the escorted group and only if the pickets are armed. Again, this reminds us that we’ve completely

forgotten just how many ships are required to form a survivable group. We’ve grown up seeing a carrier escorted by

three ships when the combat-reality is that we will need 30+ ships and that’s

before we factor in any distant picket requirements.

Countermeasures -

Japan did attempt radar countermeasures, employing chaff and radar reflective

kites, though with limited success.

Today, sophisticated radar countermeasures would, undoubtedly, be

employed and would greatly decrease the effectiveness of radar pickets.

Expendability -

It was understood that the pickets would be spotted and attacked. Recommendations were made that the picket

ships be the smallest possible ship that could perform the function so as to

make losses ‘acceptable’.(4) This is a

concern for us, today, given that our smallest surface ship is the

multi-billion dollar Burke. Even the

future frigate is a billion-plus dollar ship and cannot be considered

expendable. The Navy’s vision of small

unmanned vessels may be appropriate in terms of cost, if they can resist the

temptation to gold plate them.

Summary

Future naval warfare will, without a doubt, feature massive,

saturation missile attacks and the US Navy has not devoted any attention to the

problem. The Chinese Type 055 destroyer/cruiser,

for example, has 112 VLS cells that can be loaded with anti-ship missiles. Okinawa offers historical lessons that we can

apply to our defensive efforts. The Navy

plans to employ unmanned picket vessels to accompany and escort carriers and

surface groups but the pickets are going to be unarmed and unarmored. A peer enemy will have hundreds or thousands

of missiles available for attacks and unarmed/unarmored pickets won’t stand a

chance and will be quickly eliminated leaving the core group with no early

warning and no early engagement.

The Okinawa pickets provided early warning but also early

engagement and fighter direction assistance.

In other words, the pickets were not just passive observers, they were

active combatants and, as such, managed to tie up many of Kamikaze aircraft

that penetrated the CAP screen. We need

to give serious thought to reconfiguring our pickets beyond their purely

passive sensing role and make them combatants.

That requires arming them with short/medium AAW weapons and building

them with an appropriate degree of armor.

The Okinawa pickets clearly demonstrated the value of armor.

Given the relatively small number of kamikaze aircraft that

penetrated the CAP, the damage and destruction they wrought was stunning and

modern anti-ship missiles are likely to be even more destructive given the

unarmored and weakly built ships that make up today’s fleet. We need to alter our ship design philosophy

and start designing ships for combat, not peacetime cruises.

The Okinawa example pointed up the need for massive numbers

of ships to stand up to high end saturation attacks and to compensate for sunk

and damaged ships. Okinawa, alone,

involved over 600 ships, not counting hundreds of additional, lesser craft such

as LCIs, LSMs, LSTs,

LSVs, etc.

This one operation used 2-3 times more ships than the entire current US

Navy. We’ve forgotten what is required

to wage high end war.

Frankly, the Navy’s vision of unmanned, unarmed, unarmored

picket/escort ships is ludicrous and combat-useless. They’ll be instantly eliminated in any attack

without accomplishing anything. Only if

we can make them powerful enough and tough enough to survive long enough to

accomplish their purpose will they be combat-useful. However, this requires a complete rethink of

the entire concept. Unfortunately, just

like the LCS, the Navy has already committed to the design and acquisition of a

fleet of unmanned vessels without any understanding of their capabilities and

vulnerabilities. As with the LCS, we’re

committed to buying a fleet of worthless vessels. Is the Navy truly incapable of learning from

their mistakes? It would seem so.

____________________________

Related side note:

The radar picket system was established to provide early

warning and early defense against the kamikaze saturation attacks. The ultimate development of radar picket

ships was the high speed, nuclear powered submarine USS Triton which could

perform picket duty and dive when threatened.

The obvious problem with this tactic is that the pickets could be kept

underwater and ‘mission killed’ by a single aircraft. In addition, a submarine has no anti-air

capability and cannot engage the attack, only warn of its approach.

____________________________________

(1)https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Okinawa_naval_order_of_battle

(2)History News Network website, “Kamikazes at the Battle of

Okinawa”, Joseph Wheelan, 6-Mar-2020,

https://historynewsnetwork.org/article/174496

(3)https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Radar_picket

(4)Naval History and Heritage Command website, “Battle

Experience Radar Pickets and Methods of Combating Suicide Attacks Off Okinawa”,

https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/b/battle-experience-radar-pickets.html

(5)https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Okinawa#Military_losses