For generations, we’ve built multiple aircraft at a time and had many more waiting in the wings of industrial research and development. Now, however, we’ve devolved to the point where we produce only one new aircraft every forty years or so. Consider the frequency of introduction of new Navy combat [meaning fighter or attack] aircraft as demonstrated in the tables below. I’ve tried to list them all but I’ve likely overlooked one or two.

|

|

Introduced |

|

F4F Wildcat |

1940 |

|

TBM Avenger |

1942 |

|

F6F Hellcat |

1943 |

|

SB2C Helldiver |

1942 |

|

F4U Corsair |

1942 |

|

F7F Tigercat |

1944 |

|

F8F Bearcat |

1945 |

|

A-1 Skyraider |

1946 |

|

FH Phantom |

1947 |

|

F2H Banshee |

1948 |

|

F9F Panther |

1949 |

|

F7U Cutlass |

1951 |

|

F9F Cougar |

1952 |

|

FJ-2 Fury |

1954 |

|

A-4 Skyhawk |

1956 |

|

A3D Skywarrior |

1956 |

|

F3H Demon |

1956 |

|

F11F Tiger |

1956 |

|

F8U Crusader |

1957 |

|

A-5 Vigilante |

1961 |

|

F-4 Phantom II |

1961 |

|

A-6 Intruder |

1963 |

|

A-7 Cosair |

1967 |

|

F-14 Tomcat |

1974 |

|

F-18 Hornet |

1983 |

|

F-35 Lightning |

2019 |

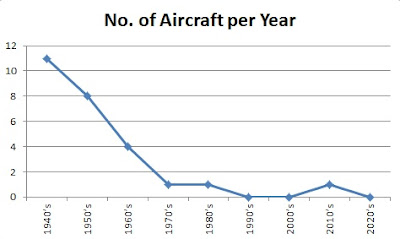

Now, if we take that data and tabulate the number of new aircraft introduced by decade, the declining frequency trend jumps out, as shown in the table below.

|

Decade |

Number of New Aircraft |

|

|

|

|

1940’s |

11 |

|

1950’s |

8 |

|

1960’s |

4 |

|

1970’s |

1 |

|

1980’s |

1 |

|

1990’s |

0 |

|

2000’s |

0 |

|

2010’s |

1 |

|

2020’s |

0 |

And here it is in graphical form:

As we can clearly see, the frequency of new aircraft introductions has dropped dramatically from several per decade in the 1940’s through the 1960’s to nearly non-existent now.

Incredibly, stunningly, unbelievably, we’ve introduced only one new aircraft since the Hornet in 1983. That’s one new aircraft in the subsequent 38 years. One aircraft in nearly four decades. I’m going to pause for a second to give you a chance to let that sink in … … …

As a result of the reduced frequency, we’ve gone from having multiple aircraft to choose from and new technology introductions occurring on a regular basis to one mammoth aircraft program every 40+ years and with no possibility of significant new technology introductions. All we can do is apply peripheral upgrades around the margins of obsolete aircraft in an attempt to keep them even a little bit relevant.

We’ve lost the flexibility and adaptability that came from having multiple aircraft types to choose from. You say the F4U Corsair turned out not to be a great carrier aircraft? That’s okay, we had other aircraft to choose from and we could make the Corsair a land based aircraft where it was better suited. We had options.

Today, if we were to find out that the F-35 is not well suited for the anticipated Pacific theatre role (spoiler … it’s not!) we have no other choice. Our next new aircraft is going to be 10-20 years down the road – if we fast track it ... longer if we don’t.

When we had multiple aircraft, the aircraft manufacturers engaged in internal research and development and developed new aircraft on their own dime because they knew that new aircraft would be purchased every few years and that they had a good chance of being a provider and making sales. Now, with only a single aircraft purchased every 20-30 years, there is no incentive for the manufacturers to develop a new aircraft on their own. The odds are that they won’t get any sales and, if they do, the quantities will, inevitably, be cut and they’ll be lucky to break even on their investment.

We’ve also lost the variety that comes from having multiple manufacturers developing multiple aircraft on their own. Now, we get one aircraft and no variety. This must change and I've described how (see, "How To Build A Better Aircraft").

There's also the issue of preserving a robust industrial base but that's a topic for another post.

Hmm, I'd count the Super Hornet as essentially a new aircraft, even if it superficially resembles the older hornet. Manufacturers can't really develop new types on their own before the navy adopts it, since the price for that sort of development has also increased 10,000x since say, the 40s.

ReplyDeleteNo other country, including potential adversaries like Russia and China is capable of creating new, current generation fighters at a mid-20th century pace either, which suggests that the trend is intrinsic to the increasing complexity of modern fighters rather than poor policy on the US side. The problems with the F-35 or the old A-12 come from maladaptive design requirements instead of the decreasing frequency of new fighter buys.

"Manufacturers can't really develop new types on their own before the navy adopts it, since the price for that sort of development has also increased 10,000x since say, the 40s."

DeleteI fear you're misidentifying the problem. It isn't that the cost has increased but that the potential for recovery of the cost has DECREASED. This is a simple return on investment (ROI) issue.

A manufacturer would be happy to spend hundreds of millions of dollars developing prototypes IF they had a reasonable expectation of ROI. While the cost of aircraft prototypes has increased SO HAS THE COST OF PRODUCTION AIRCRAFT. In other words, you may have to spend a lot to create a prototype but you'll make that back many times over IF you can get a contract for the aircraft. Unfortunately, we've created a situation where the chance of recovering the investment is very poor. Only one new aircraft in 40 years and only one company gets to produce it and earn money - no wonder companies are reluctant to build prototypes.

Now, let's think about WHY modern aircraft are so expensive. It's because we make them overly complex. Because we only produce one aircraft every 40 years, we try to make it a do-everything wonder-machine. If we would keep it simple, we could afford more aircraft. If we want a fighter, let's build a fighter, not a combination fighter/strike/ISR/tanker/ASW/EW magic machine. Let's also not burden it with useless software that tries to run the entire logistical support, maintenance, and mission planning functions of the entire program (I'm looking at you, ALIS/F-35). Strip out everything that isn't air-to-air and we'll find we have an affordable, easy to produce, easy to maintain aircraft.

"intrinsic to the increasing complexity of modern fighters"

As I've just covered, you've fallen prey to the altered belief that today's aircraft programs are normal. THEY ARE NOT! We built the F-14 in just a few years from RFP to squadron service. There is no inherent reason we can't still do that. We've just come to believe that aircraft require decades to develop and that's false. We've grown up seeing nothing but badly flawed development and acquisition programs and now we think that's normal. IT'S NOT!!!!!

The barriers to entry in 2021 are ridiculous compared to, say, 1941.

DeleteIf nothing else because technological complexity has skyrocketed.

A WWII fighter was pretty much a malformed truck, modern jets are Star Wars stuff.

This matters.

Look, I love the F-14 as much as anyone, and I definitely do believe we need a new longer ranged fighter, but integrating stealth and modern avionics is incredibly expensive and time-consuming even if we somehow manage to achieve purity of design. The F-22 that you speak highly of was optimized as a pure air-dominance fighter (although later adapted to strike roles as well), and it came out phenomenally expensive, even more so than the somewhat compromised F-35.

Delete"but integrating stealth and modern avionics is incredibly expensive … The F-22 that you speak highly of was optimized as a pure air-dominance fighter (although later adapted to strike roles as well), and it came out phenomenally expensive,"

DeleteYou're missing the reason for the cost and that reason violates every precept I've laid out in multiple posts on the subject of aircraft procurement. The reason the F-22 was expensive was that it attempted to introduce MULTIPLE new technologies into a production aircraft. These technologies included supercruise, supermaneuverability, stealth, sensor fusion, thrust vectoring, new alloys, complex flight control software, etc. None of these existed at the time. Of course the resulting aircraft would be expensive.

As I've repeatedly stated, the way to build an aircraft is to use existing airframes and then integrate existing sensors and weapons. The F-22, as built, should have been a research prototype, not a production aircraft. If/when it was perfected, it could have entered production.

The Russian SU-57 and MIG-35 are good examples of how to do it right.

DeleteCurrently the SU-57 is a 5th generation aircraft but that's not all it's supposed to be. It's been designed to become a 6th generation fighter. Not all of the technologies required for that are available yet so they started out with a version without those which is 'only' 5th gen. The design itself though appears to have been developed with those future technologies in mind. Which makes sense.

Some they will be able to add to existing airframes (like the new engines which are close to being finished), others will be implemented in future builds (which is most likely an important reason why the initial production run is only 76 aircraft). The two original prototype SU-57s for example differ considerably from the production variant. Lessons learned were implemented and some additional technologies matured since then and those could be incorporated into the first production run.

The MIG-35 is perhaps even more impressive, not in combat capabilities but in design concept. Instead of using new technologies, they designed a 4++ gen aircraft using both the very best of proven and reliable technology and materials. So what if it's 'only' 4th generation? It's incredibly cheap to produce (relatively speaking) and even cheaper to maintain and operate.

There will be far less potential for upgrades, but it is about the best possible 4th gen you can get with respect to COST-effectiveness. And make no mistake, it is a very, very capable aircraft.

This is what the US should also do. There should be parallel development tracks. One focused on using ONLY proven and reliable technology and materials that have 'matured' and are therefore cheap. There should be no new gimmicks whatsoever. None at all. Not a single one. Nada.

In addition to that you have a development track where you design with future upgrades in mind, but only adding new tech gradually, not all at once.

R

'The reason the F-22 was expensive was that it attempted to introduce MULTIPLE new technologies into a production aircraft. These technologies included supercruise, supermaneuverability, stealth, sensor fusion, thrust vectoring, new alloys, complex flight control software, etc. None of these existed at the time. Of course the resulting aircraft would be expensive.'

DeleteEvery single technology you listed had already been deployed on a previous generation aircraft. Supercruise is found on plenty of 4th generation fighters like the Typhoon and Rafale, as well as arguably even the comparatively ancient English Electric Lightning. Stealth was proven in combat with the F-117 and B-2, as well as many previous experimental projects. Sensor fusion is also a feature that's made it onto 4.5 generation Eurojets like Typhoon/Rafale/Gripen, while thrust vectoring is far older and saw service on even the oldest Harriers. Many of the alloys used on the F-22 were newly developed, but the heavy usage of titanium and composites was pioneered far before that on the SR-71. While the F-22's software is certainly impressive, the big jump in digital fly-by-wire capabilities came with the prior generation F-16. All of these technologies were already somewhat mature, but integration into one fighter is still immensely costly in time and cash.

The guy hyping up Russian fighters is also overstating the case. The SU-57 being '6th generation' is just marketing buzz, as the actual jet has run into massive developmental delays, it still doesn't have the desired engines, and Russian industry is struggling to provide the all-azimuth sensors and avionics that have been touted.

The MiG-35 is ever worse off, despite being a far less ambitious project. Domestic orders have been laughably tiny, and it has totally failed in the primary objective of becoming an export success. Operating costs for frontline squadrons operating the type have increased to nearly that of the larger and more capable Flanker, while the production model lacks the previously promised AESA radar and thrust vectoring.

"Every single technology you listed had already been deployed on a previous generation aircraft."

DeleteSorry, no. Check the dates on various technologies. For example, the YF-22 tested its supercruise in 1990 whereas the Typhoon first flight was 1994 and Rafale first flights were 1986-1991. Thus, the supercruise certainly didn't exist in any kind of finished form. The most that can be said is that the technologies were somewhat developed concurrently.

Similarly, the F-22 stealth involved new technologies compared to the F-117 and B-2 with more reliance on coatings and materials as opposed to shapes.

And so on.

"The guy hyping up Russian fighters is also overstating the case ..."

DeleteFirst, be polite.

Second, talk about spin! The delays have been far shorter than those for US aircraft projects, so if the Russian delays are 'massive', then what are those of the US?

Secondly, what you try to spin as a negative was actually a positive. They didn't have some of the technology they needed yet, so they delayed, unlike the US. Result is that the Russian now have a jet that is far more promising and capable then the disaster that is the US F-35.

I did already mention the engines did I? Again you are spinning a positive into a negative. It's a 5th generation fighter WITH THE CURRENT ENGINES. And even better engines are just around corner.

The same for the rest of your comment. You're simply repeating what I said but decided to spin it negatively. I wonder why. (And by the way, what percentage of high end components is actually build in the US? Hint, it's far, far less than what the Russians build themselves).

You seem to make a mistake that I notice is made rather often among many westerners and among Americans in particular. You (and your experts/analysts) rather persistently assume that whatever 'the buzz' is about a foreign weapon system, it must be PR or spin or otherwise exaggerated. You think that because that's what the US and US producers always do. They nearly always exaggerate capabilities and/or make promises they can't keep. So you assume that everyone else does that do. They don't.

The Russians typically do the exact opposite. They have a persistent tendency to understate their capabilities.

In the US weapon systems are not primarliy designed, build and marketed for their usefulness in combat but for commercial purpose. Weapons in the US are developed and build for private profit, not for war. The latter is a secondary purpose.

Because of this, weapons are heavily marketed with lots of spin, PR and false promises to get more orders and make more profit. Once the orders are in, the buyers are usually stuck with it so the (western) producers keep getting away with it.

Russian weapons are built for war, not for profit. A key element in being prepared for war is not to openly advertise your capabilities to the enemy. In other words, don't brag about how good your stuff allegedly is. It's also why export models of vital Russian systems are typically considerably downgraded compared to the variants in Russian service.

There is another cultural difference between the US and Russian. Like it or not, the US has a culture of being loudmouths with lots of posturing. Making yourself look 'big' and powerful is seen as a sign of strength. (Which leads to a lot of exaggerating and false claims btw). Russians are far more reserved and quiet. They don't like braggarts. It's a cultural thing. To them, the louder you are, the weaker you look. Kind of the opposite of how it is seen in the US. It's like one dog who barks all the time, while the other one sits quietly waiting for the right time to bite, should it become necessary.

Finally, and back to the topic at hand. You managed to completely and utterly miss the point of my post. You can have your opinions on the quality of Russian systems, just like I have mine. They're moot.

The point is the different kinds of development tracks they have, and the design philosophies (in other words, not the CONTENT of the designs, but the PROCESS of designing) that come with it. Had the US followed those the last three to four decades, you wouldn't be in the mess you're in now.

There's plenty more to pick from. Take the evolution of the SU-27 to the SU-30, the SU-34 and the SU-35. Or the latest incarnation of the MIG-29 which like the 'Super Hornet' might as well qualify as a new type in it's own right.

Maybe, just maybe, you could learn a thing or two from the Russians.

R

"Take the evolution of the SU-27 to the SU-30, ...

DeleteMaybe, just maybe, you could learn a thing or two from the Russians."

I don't follow Russian aircraft development processes so I can't say whether the process you describe is true or not but I do note that the evolutionary development you ascribe to Russian aircraft is exactly what happened with the Hornet to Super Hornet (as you noted). The only difference is that the Hornet development was not planned but was borne out of a lack (failure) of other choices. I'm dubious that Russia actually planned for an evolutionary process but it's possible.

I would also note that many/most Russian weapons pronouncements are quite overstated with ridiculous claims of success. For example, historically, their SAM claims are near 100% kill rates and yet their actual performance is abysmal (Vietnam, Desert Storm, etc.). Based on observed ratio of claims to actual performance, I routinely discount Russian claims by 50% to 80%. To be fair, US claims are almost as bad.

All that aside, you bring up an interesting point about the process of aircraft development. In theory, an intentional evolutionary design process has advantages. The reality, however, is that unless the evolution is a definite item and in the short term, the required upgrades often do not happen. The US Navy is famous for promising mid-life upgrades and modernization and refusing to actually do them.

Another problem with upgrades is that some/many upgrades cannot be done. For example, the Hornet simply cannot be upgraded to stealth standards to any appreciable extent. Even the attempt to add an IRST to the Hornet is a questionable, marginal improvement, at best.

Now, an example of a planned evolutionary upgrade that occurred was the engine for the F-14. It was known that the F-14 was underpowered originally and needed a better engine and, eventually, a better one came along and was installed. That, however, is the exception rather than the rule.

So, an evolutionary process is theoretically possible and might be helpful but the practical aspects seem to render it moot, generally. Whether Russia actually follows such a process, intentionally, I don't know.

"Weapons in the US are developed and build for private profit, not for war. The latter is a secondary purpose.

Russian weapons are built for war, not for profit."

Let's be objective and fair. Russia heavily promotes its weapon systems for export as does the US. For example, Russia heavily promotes sales of its various SAM systems. Diesel SSK submarines are another heavy export weapon system. And so on.

"culture"

Please omit further discussion about politics or culture and stick to the military aspects. Thanks!

"Let's be objective and fair. Russia heavily promotes its weapon systems for export as does the US."

DeleteThis is true, but I don't think the Russians do stuff like the F-35 built-in-every-state scheme, for example.

They build weapon systems for war, and only later sell them (well, neutered version of them) to make money.

In the USA, weapons are increasingly built for corporate profit, then sold/given away to other countries for political/economical reasons.

"I don't think the Russians do stuff like the F-35 built-in-every-state scheme,"

DeleteWell, they don't have 50 states, so …

They do, however, negotiate a lot of license builds in/by other countries. Not exactly the same thing but ...

The point is that they do it after the weapon is built, not before.

DeleteSee the ultra-complex multinational F-35 consortium, for example.

Russia would have just built the plane then sold it abroad.

Now, to be fair I'm not a super expert on Russian procurement so they might do stupid stuff I'm not aware about.

The Russians have been doing joint-development stuff with India in the last decade. BrahMos is the biggest visible success, but other programs like MTA have been killed.

DeleteRussian development is very evolutionary. They utilize lots of prototyping concepts, alot of stuff never makes it to production.

DeletePlenty of Ships, planes, weapons, etc have been designed, studied, and rejected for various reasons before they even reached discussions for prototyping.

I recommend ComNavOPs, that you look into their past development processes, I feel they aline with your views.

"If nothing else because technological complexity has skyrocketed.

DeleteA WWII fighter was pretty much a malformed truck, modern jets are Star Wars stuff."

Yes and no... Sure todays stuff is complex, but in the 40s, a fighter was equally complex. The internal combustion engine was still relatively new. It had seen less than a half century of widespread use. Machining capabilities were crude, and mass producing engines that would live for long periods was in retrospect, amazing. Calculations to figure out airworthiness were done with pencil and paper, and aerodynamics were barely understood. Metallurgy was still being sorted out. Heck we were still riveting ships together!! So while todays tech is science fiction from a 40s perspective, 40s tech is also science fiction from an 1860 perspective. Its different, yet the same....

When did our acquisition commands stand up? I am thinking Army stood theirs up formally in the 80's but had an informal approach starting in the 70s. NAVSEA was in the 70s and then I believe SPAWAR was 80s. seems the red tape at these commands contribute greatly to the inability to be agile in our services anymore

ReplyDeleteThe F-35 is two different but slightly related aircraft.

ReplyDeleteExcellent topic, ComNavOps. I think the Navy has gone absolutely berserk with the notion of one airplane to fit all uses, so we end up with aircraft that are not as good for any use as single-purpose aircraft would be. In my day we operated three different fighters (F-4, F-8, later F-14) and five different attack aircraft (A-3, A-4, A-5, A-6, and A-7), each with a specific purpose, and each better at that purpose than any sort of "one size fits all" would have been. We managed the spare parts and logistics needs for all those different types, and with 3-D printing that process should get easier.

ReplyDeleteI like taking existing, proved airframes, adding existing, proved technology, and updating as newer and better technology proves itself. What needs do I see?

For carrier air wing:

VF: 3x12 air superiority fighters/interceptors, long loiter time, long-range sensors and weapons, good visibility and handling for inevitable dogfights

VA: 1x12 attack aircraft, long legs, stealth, and a big weapons load

VS: 1x12, 6 patrol/ASW, 5 tanker, 1 COD

AEW: 6

EW: 6

Helo: 7, mixed types, plus 1 V-22 (not a fan, but the Navy loves them)

Total 80 aircraft. For smaller, conventional CVs, drop 1 VF or VA squadron (depending on mission), cut back VS to 8 (4 ASW/patrol, 3 tanker, 1 COD), and drop 2 EW and 2 helos, for a total of 60 aircraft. Add up to 5 drone tankers as they become available. Don't use drones for combat missions until the technology improves dramatically.

If we convert LHAs/LHDs to "Lightning Carriers" for interim use until the CVs enter the fleet (10-15 years, about the time that the Lightning Carrier lives would be expiring), they would carry 35-40 aircraft, probably 2x12 F-35B and 10-16 helos/V-22s.

Aircraft to meet needs:

VF: Maybe Super Hornet, although something with longer legs would be better. Not F-35. Maybe something between F-14 and F-22.

VA: We really don’t have anything now. Maybe start with A-6 or A-12. This will need to be a big airplane, so anything we can do to make other aircraft smaller would help with flight deck and hangar space.

VS: If the S-3s can handle modern ASW electronics, update and bring them back; otherwise pretty much starting from scratch here.

AEW: E-2s for now, but we need to start the replacement pipeline.

EW: Since the F-35 has pretty advanced electronics, maybe adapt it. It needs longer legs and would probably be better with an NFO to operate the electronics, so maybe put a second seat where the F-35B lift fan is and convert the bomb bay to more fuel and electronics. The F-35I might be a good starting place.

Helo: Go with what we have for now.

Except for EW, I don’t see a fit for the F-35C. I would convert existing F-35Cs to EF-35s, building the future F-35Cs as F-35Bs to operate off the Lightning Carriers, transferring the Marines F/A-18s to the Navy to fill in shortages there, and telling Marine air to focus totally on getting Marines ashore and providing CAS, and leave air superiority to the Navy.

Marines:

Marines need a "Marine A-10," a rugged, reliable, easily maintained aircraft, with good performance low and slow, a big gun and a heavy weapons load, able to operate off carriers, preferably off LHAs/LHDs or Lightning Carriers, and short and unprepared land strips, so they can go ashore with Marines and operate close to the front. A navalized Gripen would be good, except that it does not land vertically; maybe add an angled deck to at least the newer Lightning Carriers (with enough life left to justify it economically) and convert them to CVLs; F-35B is not really this airplane, but could do in the interim.

Shore-based patrol:

As an old ASW hand, I question the shift to high-altitude ASW with the P-8. I have previously mentioned the Kawasaki P-1 as an airplane that has the ability to do conventional low-altitude ASW too. I have seen reports that it is considerably cheaper, but cheaper or not, I would like to license-build some for a mix to keep low-altitude ASW in the bag of tricks.

Although I have learned many failure of F-35 and other fighter jets, I think the key issue is ---- US is losing its R&D competency, at least in military front. One ore two weapon delay and failure is unavoidable but continue failing and delay, it speaks something greater.

ReplyDeleteApart front long, very long delay of the F-35 program, its original goal -- low cost common platform used by Navy, Air Force, and Marine has failed. Not just manufacturing costs, operational costs are also intolerably high. To most businesses, it is bearable for high capital investment(one time) but not high running cost(long term).

Initially, F-35 was designed to be an attacking aircraft (as it was first named). It was raised to current status of "air superiority" only after failure of the F-22 program. Now, F-22 has to be housed in temperature and humidity controlled hangers.

Nevertheless, Marine is happy with F-35B as it is far better than AV-8. As I read, both Air Force and Navy are not happy but Marine is happy.

Did fighting a world war from December 1941 to September 1945 have anything to do with number of aircraft introduced during the 1940's?

ReplyDeleteOf course it did … to an extent. If you look at the interwar years between WWI and WWII, there were many, many new aircraft designs so war, alone, doesn't explain the rate of new aircraft introductions.

DeleteAlso, one would think that a steady diet of US wars from the end of WWII until today would have equally stimulated aircraft development … and yet it hasn't. Our never ending wars in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Desert Storm as well as rising threats from Russia, Iran, NKorea, and China ought to be providing more than enough incentive for new aircraft designs and yet they aren't. So, to attempt to ascribe the 1940's rate of development simply to a war is inconsistent logic. We're engaged in perpetual wars today and yet we seem to have no desire to develop new aircraft.

"If you look at the interwar years between WWI and WWII . . ."

DeleteLet's remember that during the interwar years that dozens of new technologies were introduced which allowed new types of aircraft to be developed. At the same time, there was a lot of experimentation, especially in the military, just to see what aircraft could actually do. And, given the materials and construction techniques of that time, it was also far easier to build an aircraft back then.

"Also, one would think that a steady diet of US wars from the end of WWII until today would have equally stimulated aircraft development . . ."

As they say, necessity is the mother of invention. If a tool isn't up to the job for whatever the reason, you either improve your existing tool or replace it with something better. The same applies aircraft in war and in peacetime.

In WW2, we replaced aircraft when they became obsolete and developed new aircraft when the needs changed or when new technologies, like the jet engine, became available. At the same, we regularly developed newer models of existing aircraft, the P-51 Mustang is a good example.

Since WW2, we've constantly upgraded existing aircraft with better engines, electronics, and weapons in response to new threats. We've also made improvements in how our pilots are trained. A new threat in war or in peace doesn't necessarily require a new aircraft. But, when the right threat does appear, that's when we develop something new to deal with it.

As for the perpetual wars of today, if our existing aircraft weren't cutting it, they would be put aside and a replacement developed. But, with improvements, largely in electronics and weapons, they are doing just fine. Operating in a permissive environment helps too, which obviously will not always being the case.

The War on Terror has resulted some technical improvements that might not have been developed otherwise. The Remotely Operated Video Enhanced Receiver (ROVER), which allows the ground guys to see what aircraft are seeing, might be the best one of the lot. ROVER allows the ground guys to better identify targets and reduce the risk of friendly fire. The F-14Ds were fitted with the ROVER III system and the Super Hornets are similarly equipped today.

One issue not discussed is the money to develop a new aircraft or even to improve an existing one. In WW2, we were funding everything we thought would work as we had a war to win. Back then, many deals were done with a handshake and a promise. And, the acquisition process was far simpler. That's simply something we can't do today.

"And, the acquisition process was far simpler. That's simply something we can't do today." We can, we choose not to and do not have leaders willing to make the decisions to ensure that we can. Our acquisition programs are now jobs programs and nobody wants to cut them or the red tape which makes developing new capabilities quicker and less expensive.

DeleteThe Australian Loyal Wingman has flown for the first time. See https://www.thedrive.com/the-war-zone/39539/australias-loyal-wingman-air-combat-drone-has-flown-for-the-first-time

ReplyDeleteIt is also being offered by Boeing US as part of the US Airforce equivalent program. See https://www.thedrive.com/the-war-zone/39560/boeing-is-adapting-its-australian-combat-drone-for-the-u-s-air-forces-skyborg-program

But of note to this article is the speed of development by using the latest design techniques known as the Forth Industrial Revolution.

"The ATS has gone from the start of detailed design to successful flight in three years. Those are the kind of timelines we saw back in the world wars, when technology was simpler, national survival was on the line, and governments didn’t care too much about losing some test pilots in the development process."

and the implication,

"One element of digital design technologies that holds great promise for the program is that once the technologies that provide the right mix of human control and autonomy are mature and payloads are integrated into the base version of the loyal wingman, developing other variants shouldn’t be too hard. Indeed, Defence has indicated that it envisages an evolving family of aircraft of different sizes."

From https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/loyal-wingmans-first-flight-shows-fourth-industrial-revolution-in-defence-capability-has-arrived/

Things may be changing.

"I’ve tried to list them all but I’ve likely overlooked one or two."

ReplyDeleteYou missed quite a few. Some not insignificant players in the fighter/attack realm. 50s, 60s, 70s, & 80s. Their absence somewhat skews the argument and the graph:

F-86

F-100

F-102

F-104

F-106

F-105

F-111

A-37

A-10

F-16

F/A-18 Super Hornet

F-22

I've probably missed a few myself.

He's clearly talking about only carrier aircraft.

Delete"You missed quite a few."

Delete*sigh* … This is a Navy blog. We're talking about Navy aircraft.

I mean, did you really think CNOps forgot that, say, the A-10 exists?

DeleteOr F-22, super bug, etc.?

Come on.

"*sigh* … This is a Navy blog. We're talking about Navy aircraft."

DeleteSo you are. My bad. Reading comprehension and all that (skimmed over that discriminator). Mea culpa.

OTOH... Are ever declining NAVAL fighter/attack variants really a concern when only a few nations even possess carrier borne aviation? When most of those are allies flying US produced models like the F35? Thinking in terms of carrier vs carrier engagements out in the wider Pacific. Closer to shores, the mix of combatants is going to include everything that an enemy can fly... not just naval platforms.

Yes, capabilities arguments (range, mission specificity, payloads, stealth, tanking, ECM, etc.) arguments are valid, but perhaps the longevity/production gap argument is not all that important. When our potential foes own damn few seaborne squadrons to begin with.

Yes, we've fielded fewer new types and employed them across longer arcs of service life. But that may just be irrelevant. As long as those airframes remain viable for desired missions.

There's been a similar historical trend with regard to introduction of armored vehicles since WWII. We (and everyone else) once simultaneously fielded multiple models/classes of tanks. But eventually arrived at near universal equipping with only 1-2 models. Which, like modern aircraft, are also extremely complex, high-tech, and costly. In 1945, the Army employed (IIRC) 8 different tank types, plus 2 different turreted tank destroyers. Towards the end of the Cold War... 3-4 models. Today, we are down to one basic tank design (in several upgraded variants).

Perhaps one glaring reason for fewer current USN F/A types is that our greater national defense/economic focus has been on USAF platforms. Because our post-WWII strategic aviation focus is based upon on a combination of both forward ground basing & long ranged USAF platforms. Not Navy ones.

I'm worried less about a multiplicity of barely affordable types and more about declining combat radius of Naval types since the Cold War. Which deficiency will (probably) be soon offset by ever longer ranged air launched stand-off weaponry.

Another point to consider is the winnowing/conglomeration of firms capable of producing designs. The landscape is vastly different than it was in the 50s/60s/70s. When you've only got one or two vendors offering candidate airframes, there's an inevitable trend to seeing only those types in service a decade or three later.

Apologize for my initial reading error, but really don't see the criticality of the issue. Fewer extant models is not in and of itself an issue... as long as the models we do have can accomplish the job. Whether current choices are optimum is another debate.

I'm just a dumb retired grunt. With a hobbyist affinity for things naval & aviation. Here to learn. Good blog and good discussion.

"Thinking in terms of carrier vs carrier engagements"

DeleteWhen have I ever mentioned carrier vs carrier battles? The answer is never as I don't consider that a likely scenario. In fact, I consider it to be a vanishingly remote possibility at least for the next twenty to thirty years. Therefore, you're missing the role of carrier aviation which, as I've stated many times, is long range air superiority which brings us to your next, related statement:

"Fewer extant models is not in and of itself an issue... as long as the models we do have can accomplish the job."

And … the models we have cannot even remotely accomplish the job. Neither the Hornet nor the F-35 is a long range, air superiority fighter and none of the other carrier options … uh, … oh, wait … there are no other carrier aircraft options … which was the point of the post. No options means no flexibility and no adaptability.

As you noted (or maybe you didn't?) in the post, the problems with so few new aircraft are many. For example, the introduction of new technology over a 40 year span becomes difficult to impossible with no new aircraft coming along. We see this with the Hornet. It simply can't be upgraded to modern standards. We can play around the periphery and give it a better sensor or new missile but we can't give it the range, stealth, speed, maneuverability, sensor fusion, etc. that is need to be a true, modern air superiority fighter.

There's also the aspect of the industrial base which is steadily shrinking due to the lack of new aircraft introductions. I fear you're confusing cause and effect in this. The contraction of the aviation industry is due to our movement towards fewer aircraft not the other way around.

Our refusal to introduce more frequent aircraft has left us with a near-obsolete, compromised aircraft and a modern-ish fighter that is ill-suited to the Pacific theatre and which the Navy has been extremely ambivalent about, from the start. We have no other options. Does that sound like a good situation?

"When have I ever mentioned carrier vs carrier battles? The answer is never as I don't consider that a likely scenario."

DeleteYou didn't. I did. When I see a peer power continually growing an ever larger and more capable carrier force, I do find it likely. Perhaps not in the immediate future, but in the one where we eventually get our asses kicked in the South China Sea.

I believe it's myopic to dismiss overt display of physical intent. A growth force is neither token nor symbolic. As Angela Mayou is reputed to have said: “When people show you who they are, believe them.”

"And … the models we have cannot even remotely accomplish the job."

Agreed. 100%. That's on the USN, Congress, and every administration since Bush Sr. Think back to 1989-1993. Bush intended to slash the defense budget and the force-in-being. Desert Storm interrupted that calculus. But after the dust settled, some things were evident:

1. The USA was the indisputable global military power left standing. The USN faced no remaining viable threat outside of regional piracy and Iranian or N. Korean littorals.

2. The Soviet Empire was no longer a tactical/operational threat. Its blue water navy no longer a sea worthy force... outside of its carefully husbanded nuke boomers.

3. China was not even vaguely a blue water threat nor (according to intel estimates at that time) due to become one. "Just gonna buy that ex-Soviet carrier for a floating casino hotel don'tcha know..."

4. The new Clinton administration (and Congress) was determined to turn guns into social welfare butter and did so. The money tap for many major weapons proposals was strangled (with a few exceptions). All US services were underfinanced for the remainder of that decade.

5. That same Clinton administration viewed China as a major economic partner and even as a possible future geopolitical ally. There was little alarm over future Chinese military growth, because China's economic miracle was still nascent.

6. Back then (90s), the USN bet the farm on a stable future world and the mix of aircraft they chose to meet it. That everything was gonna be sunshine & roses. Regional policing and presence patrols. Small wars... not world wars. Long range penetration/air dominance against a peer force no longer of primary concern. Legacy fighters would do nicely.

6. Those late model USAF platforms that I mentioned competed successfully for priority over naval airframes... in the DoD budgetary wars. Cause the USAF argued that it could go anywhere in the world and deliver the mail. While not having to simultaneously fund proposed the new carriers, subs, surface combatants, etc. that the Navy also held dear. In other words... naval aviation was a lower priority in the grand scheme of things. USAF procurement directly impacted what aircraft the Navy could or could not afford.

Contd. -

Delete"The contraction of the aviation industry is due to our movement towards fewer aircraft not the other way around."

I believe the opposite is true. That industrial globalism swept the vendor field like an inevitable tsunami. Defense industry followed a naturally profitable path towards consolidation and near-monopolies. A function of profit-taking. Whether the Navy was in the market for new airplanes or not. Just the like the commercial airline market. Or the food, agro, computer, automotive, & pharmaceutical industries.

Where we are today is a result of complex factors in the aggregate, spread across both decades of time and decisions made (in good faith) about a foggy future.

Today I see the USAF pursuing next generation fighters and credible upgrades of existing platforms. There's apparently an industrial base and technology competing for their vision (and contracts). I'm just not seeing that kind of focus from the Navy. The Air Force has indicated intent to buy. The Navy has not.

I don't think the Navy knows what it wants, nor how to get there (on the aviation side of the house).

BTW: This is my favorite place to visit for "Warts & All" theorizing on naval matters. Like a perpetual electronic Red Cell brain trust. Kudos. If the CNO isn't paying attention here... he should be.

"You didn't. I did. When I see a peer power continually growing an ever larger and more capable carrier force, I do find it likely."

DeleteRecognize that I do not dismiss China's aircraft carrier aspirations. My assessment of the remote likelihood of a carrier vs carrier scenario is based on two main factors:

1. They simply don't have the capability and won't for 20-30 years. It takes time to develop both the equipment and operating expertise to engage in a carrier battle.

2. Their objectives preclude the possibility and are two-fold: one is domination of the E/S China Seas (already accomplished) and surrounding territories/countries (they're working on it), and two is establishing global strong points for expansion in the Middle East, Africa, Indian Ocean, etc.

Neither of those factors involve open ocean carrier vs carrier engagements; the former doesn't require it and the latter can't support it.

For the next 2-3 decades, their carriers will remain inside the first island chain (peacetime propaganda voyages notwithstanding) where they can be supported by land based air. Thus, no carrier vs carrier duels.

Quite frankly, I am far more concerned by the abjectly poor quality of the newer aircraft than I am by their frequency of introduction, although the two may well be related. Efforts to save costs by producing multi-role aircraft have routinely resulted in out-of-control costs and aircraft that did not perform in any role as well as a single-role aircraft would have. How many times do we have to do this before we realize that this is not the way to go?

ReplyDeleteThe carrier air wing needs 1) air superiority fighters/interceptors, 2) long-range stealthy attack aircraft, 3) ASW/maritime patrol aircraft, 4) AEW aircraft, 5) EW aircraft, and 6) tankers, plus helos to assist with the ASW, SAR, and other missions, and each of them needs to be a separate airplane. Other than forced, there isn't that much commonality. It may be helpful for them to share some systems, but they need to be different airplanes. And the F-35 is none of them.

Marine air needs to turn the air superiority mission back to the Navy and focus on transporting and support Marines as part of a raid, strike, or assault. They need a "Marine A-10" that is none of the above.

That's seven different aircraft, plus the various helo needs. One size does not fit all, or for that matter any.

I think that these problems come from

DeleteShort term - poor project management from defense industry. Rather than face very tough "market", many people usually buy their excuse - not enough money.

Long term - drop of US science and engineering competency. Less and less smart high school graduates choose STEM as their careers. This has been happening for at least 20 years. Sorry, politically incorrect but harsh reality, secondary talents cannot perform as first tier ones.

Great analysis CNO... I think we would see similar trends looking at ships and classes...

ReplyDeleteMy humble addition to all the well-informed replies to this posting is a concern that the navy has fallen so far behind that we can't afford to catch up.

ReplyDeleteMy personal belief is that one of the highest (possibly THE highest) priority to fix is the replacement for the F14.

Our carriers are not really all that capable without a long range fighter with the ability to keep enemy surveillance and strike aircraft from getting targeting info on them.

I don't have any intimate knowledge of the subject, but a naval version of the F22 seems like it would fit most of the needs. The line could be started back up and the air force could just use navalized F22's.

The problem is that they cost about $200 million apiece. To put 24 each of these in 10 carrier air wings would cost $48 billion.

I don't see how that can be done at this point.

Lutefisk

I will tell you where a big problem lies. In my day we had these aircraft in numbers:

ReplyDeleteA-3 (going out) made by Douglas

A-4 made by Douglas

A-5 made by North American

A-6 made by Grumman

A-7 made by LTV/Vought

F-4 made by McDonnell

F-8 made by LTV/Vought

F-14 (coming in) made by Grumman

S-2 (going out) made by Grumman

S-3 (coming in) made by Lockheed

E-2 made by Grumman

P-3 made by Lockheed

So the manufacturers represented included Grumman (4 airplanes), Douglas (2), LTV/Vought (2), Lockheed (2), North American (1), and McDonnell (1)—six manufacturers for 12 aircraft. We used to laugh and call Grumman the Navy’s “pet manufacturer” since it built so many different aircraft for the Navy but none for the Air Force.

Today we have:

F/A-18 made by Boeing

F-35 made by Lockheed Martin

E-2 made by Northrup Grumman

P-3 (going out) made by Lockheed (now Lockheed Martin)

P-8 (coming in) made by Boeing

So now we have five aircraft (one on its way out) made by 3 manufacturers—Boeing (2 aircraft), Lockheed Martin (2, but 1 on the way out), and Grumman (1).

In the VA/VF world we compressed 8 aircraft made by 5 manufacturers to 2 aircraft made by 2. We have no more carrier-based ASW/patrol aircraft, so 2 aircraft made by 2 manufacturers (really 1 of each since the S-2 was on the way out) replaced by zero. We have the same one AEW aircraft made by the same manufacturer, and 2 land-based ASW/patrol aircraft made by 2 manufacturers (one on the way out, although its manufacturer now makes a fighter). Northrop Grumman has gone from Navy’s pet manufacturer to maker of one airplane type (which is now 60 years old).

Basically, we are sole sourcing everything to a Boeing/LockMart oligopoly. And that’s not a way to cut costs or drive quality.

Gone are the days when what Douglas could charge for an A-4 was constrained by what LTV/Vought charged for an A-7. Or when we could mix high-end F-4s with low-end F-8s to reduce the cost of the fighter community. And nothing has the legs that an A-5 or A-6 used to have, so carrier strike is gone as a viable mission.

From an operations perspective we have no diversity and from a cost perspective we have no competition. OK, I’ve read all the bean counter stuff about how efficient it is to have fewer supply chains. I’m a bean counter myself and that’s bunk. Competition will do more to drive costs down than any of their “efficiencies.” An airplane built to merge 2, 3, or more functions will do none of them as well as a purpose-built airplane. As for the supply chain argument, with the advent of 3D printing you can cut the supply chain by making a lot of spare parts right there on ship. Besides, we got along just fine with more aircraft—and more aircraft types—on smaller carriers.

The fewer different aircraft you buy, the more capabilities you will leave uncovered or poorly covered, and the fewer manufacturers you will have, meaning less competition and higher prices. It’s kind of basic economics.

We need to get competition back into the picture, both to give us more varied capabilities and to contain costs. But part of the problem with consolidating aircraft has been that, with fewer aircraft types, you inevitably end up with fewer manufacturers and less competition. Lockheed and Martin have merged. Northrop and Grumman have merged. Douglas, McDonnell, and Vought have merged into Boeing.

The only thought I’ve had is maybe do new aircraft buys with the proviso that if you make a credible bid but lose, you get to make so many of the proposed buy of whatever aircraft wins. That reduces the risk for manufacturers and gives an incentive for more bidders. For example, in the F-22/F-23 fly-off, LockMart won but because Northrop produced a credible competitor, they would get to make 25% of the ultimate number purchased. Or maybe make one for the Navy and the other for the Air Force.

If we had LockMart, Northrop Grumman, and Boeing fully competing on each new aircraft, we’d get better aircraft for less money.

Not only that, imagine the amount of jobs they could actually generate for the industry. That's how you solve the job issue, through large companies competition!

DeleteAnother thought that comes to mind about competition is the possibility of getting some license-built foreign designs into the mix. I look back at the Air Force tanker fiasco. If they had just let Boeing build half and Airbus USA build half, they would have two different aircraft that each had advantages in certain situations. I have also commented previously about the P-8. With it, we are effectively out of the low altitude fixed wing ASW business (we got rid of S-3s a while back). I haven't done ASW in 50 years, so maybe all this new stuff really works, but given the track record I don't think that's the way the smart money bets. Kawasaki's P-1 has 4 engines and can still do low level ASW. I think it would be helpful to have some in the mix. They are also reportedly significantly cheaper, although as ComNavOps has noted often, getting reliable cost data on anything is dicey at best. But if Kawasaki licensed it to, say, Airbus USA, and they got half the order, we would have more different tactics available and a constraint on price that does not exist now.

ReplyDeleteIt does seem to me that the only way we are going to get costs down is increasing the number of bidders. A sole source contract for a single airplane to do multiple tasks is going to produce an inferior airplane for each task, and at the same time it is going to make you a prisoner to costly change orders. Being able to say, "If you drive the price of the F-4 to high we will just buy more F-8s," or, "If you drive the price of the A-7 too high we will just buy more A-4s," is leverage the Navy doesn't have any more. Of course when congress gets involved, maybe a lot of that leverage goes away. But I'll take what leverage I can get.

Go back to the Boeing tanker. It has experienced a number of delays and problems. If Airbus were pumping out KC-47s and they were working fine, there would be huge pressure on Boeing to get on the stick with the KC-46. Same for vice versa. That's how you get costs down.

All the attempts to make one aircraft do multiple jobs simply kill off competition on the supplier side, and in so doing destroy any cost savings that might have been achieved. If I'm building a $100MM airplane for the Navy, sole source, then there is noting to stop me from finding change orders to jack the price to $120MM. If you and I are building two different airplanes, then my $100MM airplane keeps you in check and you keep mine.

Had a thought, not really thought the whole thing out so the idea has plenty of holes, I know!

ReplyDeleteSo we all know we need more competition, not sure about how much foreign designs can help when they need to ally with a US BIG defense company to bid, just giving more work to LMT, BA or NG really doesn't help much apart maybe some black world work, civilian companies aren't intetest for a whole bunch or reasons....so my idea is to try the bottom up approach. Let's create a "tool box" that meets DoD standards and pushed by DoD to help smaller companies get into the supply chain, then current or new entrants could just use these suppliers and maybe get points towards DoD contracts. Basically create a bigger eco system of engines,radar, electronics, composites,etc....this would help both manned and unmanned systems. So instead of helping the big 3, we need to help 2 or 3 levels down from level 1 big boys and create more opportunity there... Just my 2 cents....

I find it interesting that the US Airforce is going back to a tried a true fighter for replacement of the F-15c/d/e variants. It looks like they are preparing to buy in bulk the F-15EX.

ReplyDeleteI wonder what this decision will have for influence on Navy airframe purchases? This might indicate that a capability isn't always wrapped up in "stealth" especially when I suspect stealth isn't all that has been advertised as.